In this three-part series, ATRL’s Ayesha Ninan unpacks Formula 1’s long journey towards destigmatizing mental health as teams and drivers navigate the intersection of performance and well-being.

Formula 1 is one of the most grueling sports in the world, not only for the drivers but also for the teams on the road and at the factories and offices worldwide. Teams work under high pressure and tight deadlines while juggling constant travel, precarious job security, and, for the drivers, the risks of driving at top-line speeds.

For years, mental health remained a silent concern within the realm of motorsport. However, as global awareness of the importance of mental health grows, attitudes within Formula 1 have also shifted in the last decade.

In 2014, Mercedes hired a psychiatrist, Dr. Ceri Evans, to help the team manage the pressure to maintain their dominant season. At the time, Lewis Hamilton insisted that he would not go to him for help.

Lewis Hamilton (Photo via @MercedesAMGF1 on Twitter)

“I’ve never had it, never needed it, and will never have it,” said Hamilton. “So we’ll never speak of it again unless I start going crazy. For me, as a driver, it’s not something I feel I need because since I was eight years old, I’ve won every championship I’ve competed in, and all I’ve needed is me and my family.”

Hamilton’s statements epitomize where the perspective on mental health stood for drivers in Formula 1 a decade ago. While team administrators had begun taking the mental health of their employees seriously, drivers still felt the need to portray a tough image.

Drivers begin go-karting at ages as young as six years old. Many drivers who progress to racing cars move to Europe to be at the epicenter of the sport in their pre- or early teens. With the financial liabilities involved, these young drivers are all too aware of what is on the line and the sacrifices their families are making for them.

McLaren’s Lando Norris has discussed his doubts about himself during his career’s early days, reminiscing, “I didn’t believe in myself, that I was going to do a good enough job basically, and then I didn’t know what I would do if it didn’t go well.” He told Mind, the mental health charity,“But in sport, because no one wants to give the opposition an edge or show any weakness, we don’t talk about mental health as much as we should – and we really should.” He goes on to note, “It’s something that affects us all, but it’s equally something people don’t feel like they can talk about.”

Jenson Button, the 2009 Formula 1 World Champion has also said “Formula One is a very macho environment, and so you don’t admit to things like that.”

Creating conditions for young drivers to have support is necessary. Pirelli Motorsport’s Head of Marketing, Marta Gasparin talks about the scholarship programme she developed for young drivers at Porsche Italy and how it included mental coaching in addition to workouts and media training, which was not a concern fifteen years ago. “At the time, no one was talking about mental health,” she remembers, “I had to fight with some people around me to make them understand how important this is, especially for young drivers.

Young drivers can find success at an early age, but a rise to the pinnacle of motorsport does not guarantee long-term success. Drivers Daniel Ricciardo and Nyck de Vries experienced disappointing setbacks in recent times. After a number of unfortunate career moves, Ricciardo found himself without a seat at the end of 2022. Nyck de Vries, a Formula E and Formula 2 champion, stepped up to the Scuderia Alpha Tauri team at age 28, which is considered late in the sport. Unable to score points, his stint lasted only ten races before he was abruptly removed and Ricciardo was brought back in to replace him. The experiences of these drivers are a reminder of the harsh realities of the sport where uncertainties and disappointments are magnified under the intense scrutiny of the public eye.

Nyck de Vries lost his seat in Formula 1 to Daniel Ricciardo in 2023 (photo via Formula 1 on X)

For drivers who are secure in their Formula 1 seat, the impact of the sport’s travel can take a toll. Teams fly from country to continent across a race calendar that is made longer with each passing year. When teams move to different continents, equipment is shipped while crew are flown according to a complicated schedule that leaves almost no room for mistakes. Drivers have to travel across different time zones from week to week, sometimes on opposite sides of the globe, and then get in a car and drive at over 300km per hour in front of millions of viewers.

“There’s a clear correlation between jet lag and then having poor performance,” Faith Fisher-Atack, the Haas physiotherapist, told The New York Times. Physiotherapist Rupert Manwaring, who trained Carlos Sainz and now works with Max Verstappen, notes that for every hour’s difference, the body needs a day to adapt but this isn’t always a luxury they can afford. He says, “We are dealing with humans, not robots.” Mercedes driver, George Russell, has commented about his personal experience with this, stating “From the disruptions of the time zone, my heart rate during a night’s sleep is on average about 25% higher than it would be when I’m in a consistent location.”

Retired world champion, Sebastian Vettel, has warned that the governing bodies must be cognisant of the toll that the sport takes on the team members as it expands the race calendar with each new season. The pressure to perform consistently while being away from home and family takes a toll that needs to be recognised by the sport. He says, “If you break a leg, you go to the doctor. It would be wise to see what prevents me from breaking my leg in the first place. We don’t seem to be doing the same when it comes to mental health though. That is a weakness of our society, because something like (mental health issues) are often seen as a weakness.”

When athletes are frank about challenging experiences, it can resonate with their audience and foster greater awareness and recognition of the struggles someone may be facing. Team Kick Sauber driver, Valtteri Bottas, has made moving statements about how exhausting his time at Mercedes was as a teammate to multiple world champion, Hamilton. Bottas pushed himself beyond healthy limits, he says, “I trained myself to pain physically and mentally.” and he admits, ”It got out of hand, and it became an addiction. No eating disorder was officially diagnosed, but it was definitely there.” It was the death of Jules Bianchi in the 2014 crash at the Japanese Grand Prix that served as a wake up call that pushed him to seek professional help.

Jules Bianchi tragically died after an accident at the Japanese Grand Prix (photo via Formula 1 on X)

Severe and fatal accidents highlight another pressure of the sport – drivers can be in a terrifying crash and must then get back in the car to continue on, sometimes even after the death of a friend. George Russell did not always pay attention to his mental health but now works with a psychologist for his on-track performance and has found that it helped him off the track as well. He has said, “It was only through those conversations that I felt like this is giving me more than just the on-track benefits. I’m coming away from these sessions feeling better about myself, feeling like there had been a weight lifted off my shoulders.”

Mercedes team principal, Toto Wolff, recognised the importance of building his team’s mental strength. Motorsport reports that he felt the sensitivity linked to mental health was in fact a “superpower” and he stated, “I think it gives you an edge in understanding yourself. If you understand yourself, it’s much easier to understand others.” Wolff himself had been seeing a psychiatrist since 2004 as a way to, he describes, “access untapped potential.” He went on to say, “Some of the most successful people are very, very sensitive, and very, very sensitive means very, very vulnerable.” In recent years, Wolff’s initiatives with Mercedes, which include hiring a well-being manager and making over 40 mental health first aiders available to company employees, were well-received.

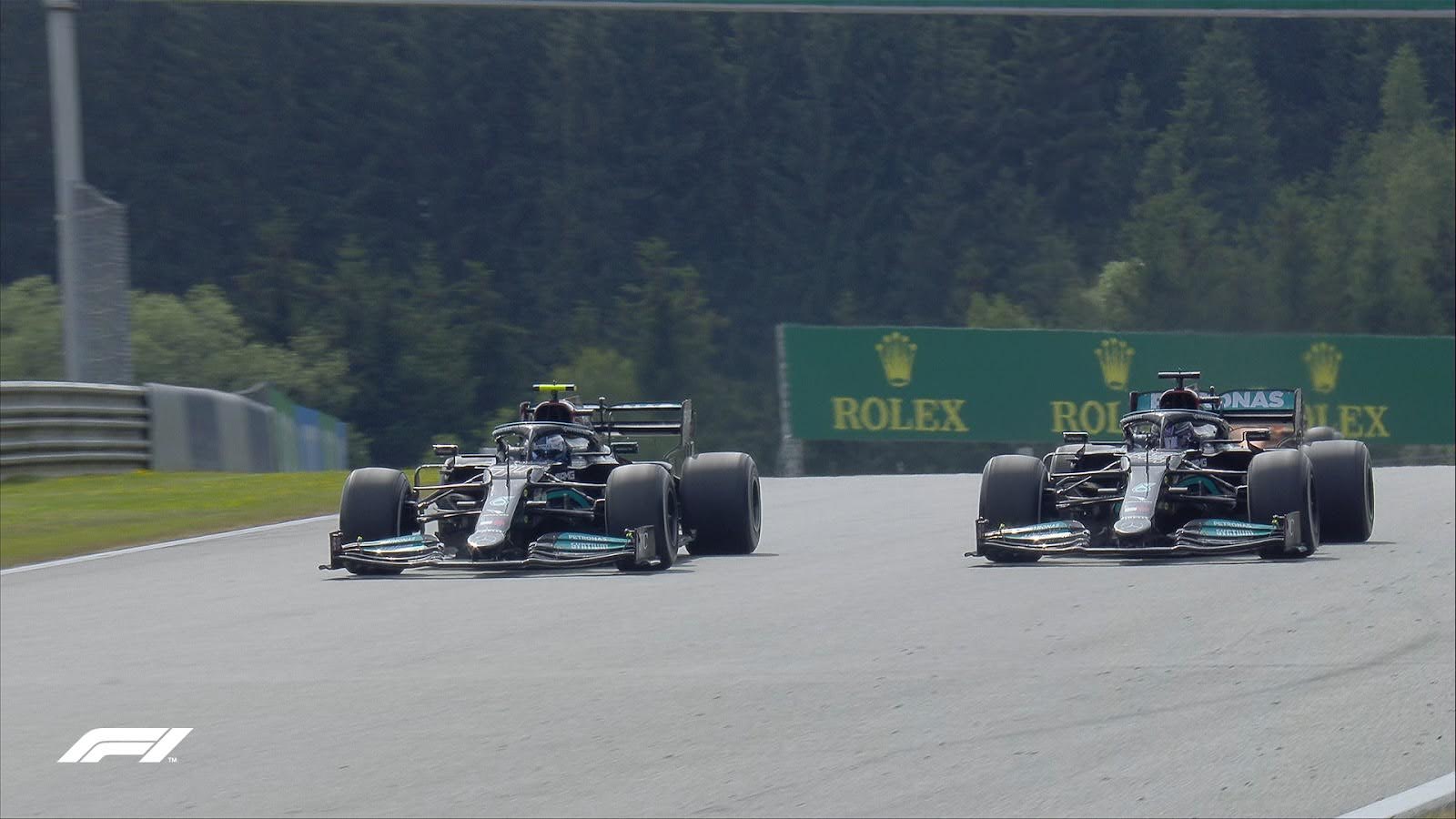

Valtteri Bottas on track with then-teammate Lewis Hamilton in 2021 (photo via Formula 1 on X)

Such developments have created a slow shift towards a more open conversation about the importance of mental health in the last decade. The sport and its members have recognised that there is a long way to go and that Formula 1 can be a part of the progress and global conversation around the importance of mental health. Broader discourse and the establishment of support systems in well-being offers benefits to both drivers and the sport as a whole; yet further action is needed to tackle existing needs across the spectrum of the sport.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Related Articles

Hitting the Apex: Sonsio Grand Prix

The Month of May launches at the iconic Indianapolis Motor Speedway’s road course. The technical track poses challenges with high speeds and strategic racing, setting the stage for a thrilling weekend. Keep an eye on championship contenders Colton Herta and Will Power. With contract terminations to debut drives, IMS promises an unpredictable race.

Hitting The Apex: Miami International Autodrome

It's Miami Race Week! Read on to know everything you need to know about the Miami International Autodrome.Miami International Autodrome is a street circuit around the Hard Rock Stadium in Miami Gardens, Florida. This “purpose-built temporary circuit” was specifically...

Josef Newgarden, Team Penske and the Push to Pass Scandal: What IndyCar Fans Should Know

ATRL’s Natasha Warcholak-Switzer details what you need to know about Team Penske’s Push to Pass violation, with perspectives from around the paddock.

Stay Up to Date With The Latest News & Updates

Interested in Writing for ATRL?

Contact us now! Fill out the form below and wait for an email from us to get started.

Join Our Newsletter

Subscribe to updates when we post a new article!

COMING SOON!

Follow Us

Follow us on Twitter and Instagram @ATRacingLine

Recent Comments